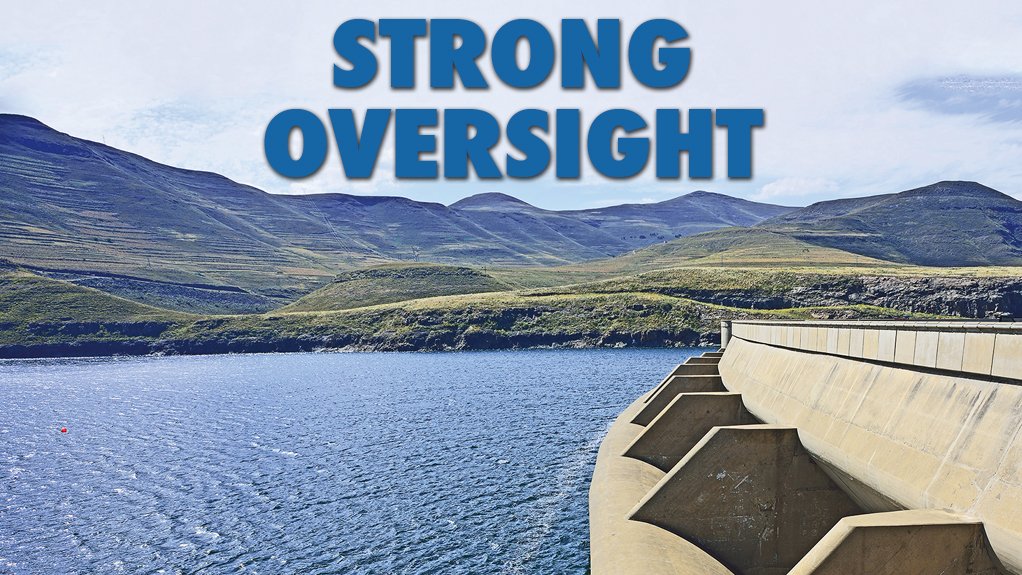

Corruption mitigation framework emerging ahead of next Lesotho Highlands phase

Significant preparatory work and construction have begun on Phase 2 of the Lesotho Highlands Water Project (LHWP), with a panel having been established to select the members for an Independent Oversight Committee (IOC) to review, maintain and monitor the integrity of the project.

The LHWP will augment the delivery of water to South Africa’s Gauteng province.

The IOC, which is expected to be functional by April 2015, will provide an independent assessment of and quality control for the implementation of the cross-border project processes, as well as advise and recommend appropriate intervention measures that will ensure the attainment of the project’s mandate.

In 2012, former LHWP CEO Masupha Sole was convicted by a Lesotho court for accepting bribes during the first phase of the project, which was completed in 2004, while the World Bank blacklisted Canadian consultant firm Acres after discovering that it had paid bribes to Basotho officials. The firm closed down shortly thereafter.

In addition, some other British and German companies were sanctioned and the Basotho officials who accepted bribes were jailed, some of whom received considerable sentences.

INDEPENDENT OVERSIGHT

The Lesotho Highlands Water Committee (LHWC) chief delegate for South Africa Zodwa Dlamini says that, given the scale of Phase 2, there are compelling reasons to establish an independent oversight function to limit the potential for more corruption and to incorporate such oversight into the project governance structure.

The LHWC, which established the selection panel to select the IOC members, has monitoring, advisory and approval powers and is responsible to oversee the implementation of the LHWP in both countries. It comprises, in equal proportion, representatives appointed by the South African and Lesotho governments.

The LHWC reports to the two governments through the Ministry of Energy, Meteorology and Water Affairs, in Lesotho, and South Africa’s Department of Water Affairs (DWA).

The IOC will monitor the implementation of the project, based on the project master plan, as well as the targets that have to be met, and will also comment on the performance of the Lesotho Highlands Development Authority (LHDA) and its contractors, as well as the LHWC.

On its establishment, the IOC will draft a detailed set of protocols as to how it will inter- act with other bodies, such as a panel of social, environmental and engineering experts, the LHWC and the LHDA.

The scope of the IOC’s assignment includes reviewing the procurement process according to the policies of the LHDA and their alignment to the terms of reference of the major contracts, verifying reports according to the portfolio of evidence, providing a report for every site visit and developing innovative evaluation tools. The latter will be presented at workshops and agreed upon by the project authorities and the LHDA.

The IOC will review and assess the measures put in place during the project to ensure the safety and integrity of the works executed, considering the best interests of the LHDA and the affected communities.

Former DWA director-general Mike Muller, who is also a member of South Africa’s National Planning Commission, believes fears of possible corruption in Phase 2 are well founded. However, he is also convinced that the aggressive action taken against Phase 1 transgressions, including the successful convictions, will send a strong signal that corruption will not be tolerated during the upcoming phase.

Muller notes that the key to avoiding corrup- tion is to empower a good project management team and ensure that there is sound professional oversight.

“The corruption challenges of Phase 1 did not have a serious impact. In fact, Phase 1B was completed on time and within budget, which is most unusual for a large project of this nature and which speaks to the firm management by the joint Lesotho-South African team,” he says.

Other measures taken to ensure that the project is free of corruption include a comprehensive anticorruption policy, which will apply to all persons and companies involved in Phase 2; a technical subcommittee, established by the LHDA board to advise and assist the board; and a cost- reporting and control system, where all costs incurred are reported to various levels of management in real time.

The LHWC, the LHDA, the State-owned Trans-Caledon Tunnel Authority, the DWA, South Africa’s National Treasury and Lesotho’s Ministry of Finance will form a finance liaison committee.

Further, regular reporting to the respective government depart- ments or Ministries and the estab- lished Parliamentary committees will also ensure a corruption-free project, Dlamini says.

PHASE 2 COMPONENTS

Phase 2 of the project will be implemented in terms of the agreement pertaining to two distinct systems – a water delivery system to augment the delivery of water to South Africa and a hydropower generation system.

LHWC chief engineer for South Africa Leon Tromp says the water delivery system comprises the Polihali reservoir on the Senqu river, in Lesotho.

The water aspect of the project is likely to cost about R10.7-billion.

The 2 322-million-cubic-metre Polihali dam will be constructed downstream of the confluence of the Senqu and Khubelu rivers, in Lesotho, and will be a 163.5-m-high concrete-faced rock-fill embankment dam wall.

The crest length will be 915 m, with a full supply level of 2 075 m above sea level. A 49.5-m-high saddle dam and a side channel spillway will also be constructed.

The Polihali–Katse tunnel, in Lesotho, will comprise a 38.2-km-long 5.2-m-diameter water conveyance tunnel, connecting the Polihali reservoir with the Katse reservoir.

“Water will be abstracted from the Polihali reservoir through two separate concrete bell-mouth intakes on the western side of the Polihali reservoir, on the Khubelu river, 3 km upstream of the confluence with the Senqu river. Access roads to the project sites, camps, power transmission lines and admini- stration centres, including social and environmental projects and programmes, will be implemented,” Tromp says.

Phase 2 may also include a pumped-storage scheme, transmission lines and appurtenant works using the existing Katse reservoir as the lower reservoir and a newly built upper reservoir in the Kobong valley.

The implementation of the pumped-storage scheme is subject to a joint decision by the two governments and is still under consideration.

Tromp says a project management unit within the LHDA was appointed in August last year and the LHWC expects that the expressions of interest for the design of the dam, the tunnel and advance infrastructure will be issued within the first quarter of this year.

A tender for the design of the infrastructure works will also be issued during the third quarter of this year.

Designs will start in January 2015 and tenders for the construction will be issued by January 2016.

As part of Phase 2, preparatory works on the road to the Polihali measuring weir and the construction of the Polihali measuring weir began in 2012 and were completed in October last year.

The socioeconomic studies as well as the in-stream flow requirements, biological and archaeological baseline studies started in mid-2012 and the mobilisation of the project management unit began in August last year.

Tromp says Phase 2 of the LHWP will augment the Vaal River System (VRS), with the total water requirement of the system at the time of completion expected to be about 2900-million cubic metres an year.

“This is assuming that we have eradicated the unlawful irrigation and implemented the necessary water-conservation and demand-management measures. The bulk of the urban and industrial water for Gauteng is supplied by the VRS and this will be about 1600-million cubic metres a year,” he states.

Meanwhile, Muller says the major challenge in South Africa will be for the respective local governments and water boards to effectively and efficiently manage the water received and to collect payments for the water supplied so that the costs of the project can be met.

He says the LHWP is an important benchmark for water cooperation in Africa but that the project, in its current form, is only possible because water users are able to pay the costs.

“Unfortunately, there are not many other potential projects on the continent that have such a large, financially strong consumer base. While hydropower projects are being implemented and funded by user payments for the energy provided, this is rarely possible for large water supply projects.

“As a result, many African countries depend on public investment to support water resource development and create the conditions for social and economic development and money is hard to find because there are many competing needs,” he says.

Meanwhile, Dlamini notes that South Africa is a member of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and a signatory to the SADC Protocol on shared watercourse systems, which fosters closer cooperation for the judicious, sustainable and coordinated management, protection and use of shared watercourses. The protocol also advances the SADC’s agenda of regional integration and poverty alleviation.

According to Article 10 of the Phase 2 agreement, the LHDA must, in the procurement of all goods and services, follow the procedures provided for in the Article, which states that all procurement processes must foster competitiveness, transparency, cost effectiveness and quality.

Further, preference will be given to sup- pliers of goods and services, including consultants and contractors, in Lesotho, South Africa, the SADC member states and then internationally, in that order, provided that the provisions of procurement processes are always satisfied.

She adds that the LHWP will create an expected increase of employment opportunities in Lesotho.

South Africans are eligible to participate at any stage of the works during the construction of the Polihali dam.

Meanwhile, Muller notes that water demand is continually increasing as populations increase, living standards improve and the economy expands.

“For the next few years, water consumers in Gauteng and surrounding areas will have to use the available water more efficiently and responsibly to avoid the risk of shortages. When it is completed, the contribution of Phase 2 of the LHWP will be to provide greater assurance that, during drought, social and economic life will not be unduly interrupted,” he concludes.

Comments

Announcements

What's On

Subscribe to improve your user experience...

Option 1 (equivalent of R125 a month):

Receive a weekly copy of Creamer Media's Engineering News & Mining Weekly magazine

(print copy for those in South Africa and e-magazine for those outside of South Africa)

Receive daily email newsletters

Access to full search results

Access archive of magazine back copies

Access to Projects in Progress

Access to ONE Research Report of your choice in PDF format

Option 2 (equivalent of R375 a month):

All benefits from Option 1

PLUS

Access to Creamer Media's Research Channel Africa for ALL Research Reports, in PDF format, on various industrial and mining sectors

including Electricity; Water; Energy Transition; Hydrogen; Roads, Rail and Ports; Coal; Gold; Platinum; Battery Metals; etc.

Already a subscriber?

Forgotten your password?

Receive weekly copy of Creamer Media's Engineering News & Mining Weekly magazine (print copy for those in South Africa and e-magazine for those outside of South Africa)

➕

Recieve daily email newsletters

➕

Access to full search results

➕

Access archive of magazine back copies

➕

Access to Projects in Progress

➕

Access to ONE Research Report of your choice in PDF format

RESEARCH CHANNEL AFRICA

R4500 (equivalent of R375 a month)

SUBSCRIBEAll benefits from Option 1

➕

Access to Creamer Media's Research Channel Africa for ALL Research Reports on various industrial and mining sectors, in PDF format, including on:

Electricity

➕

Water

➕

Energy Transition

➕

Hydrogen

➕

Roads, Rail and Ports

➕

Coal

➕

Gold

➕

Platinum

➕

Battery Metals

➕

etc.

Receive all benefits from Option 1 or Option 2 delivered to numerous people at your company

➕

Multiple User names and Passwords for simultaneous log-ins

➕

Intranet integration access to all in your organisation